Sewer overflow improvements

Introduction

This page provides a history of sewer overflows and explains what we are doing to improve the problem.

A great deal of work has been completed to help reduce overflows in Kingston. There is still a lot we will do, as recommended in the recent Water and Wastewater Master Plans Update - including information on Pollution Prevention and Control Plans, and recommended projects to 2036 to reduce sewer overflows.

Sewage overflows are a historic problem, passed on from generation to generation, along with the evolution of sewage collection and treatment. To help explain the problem of overflows, we're providing a background on how the sewer system evolved in the municipality and a discussion about the limitations of underground infrastructure.

City of Kingston wastewater collection system evolution

Prior to the 1950s

Prior to the 1950s, little thought was given to sanitary sewage aside from just getting rid of it! Original sewers were built simply to drain everything straight out to the nearest river or lake.

In the City of Kingston, this generally meant that combined sewers (to collect both stormwater runoff and sanitary sewage) were built as needed and flowed straight out to Lake Ontario or the Great and Little Cataraqui Rivers. This happened for many decades.

Perhaps long ago, there was a time when nature was able to assimilate the small amounts of human waste from settlements on the shores of the Great Lakes, but those times are gone as populations have concentrated and grown.

Original sewers were built simply to drain everything straight out to the nearest river or lake. This stone box sewer was replaced during major reconstruction activities on Princess Street in 2013. (Photo: Paul Wash)

In a nutshell - prior to the 1950’s, all of the wastewater went straight to the environment with no treatment whatsoever (100 per cent to the environment, no treatment).

1950s - Wastewater treatment is here!

Finally, in the 1950s, the municipality began recognizing the serious negative impacts of wastewater on the environment, triggered by regulations that were enacted in the Province, which required municipalities to capture wastewater and treat it. So, the City of Kingston built several things to address this problem:

- Several large ‘interceptor’ sewers generally wrapped the perimeter of the City. These intercepted the flows in the existing sewers just before they were discharged into the environment,

- A handful of pumping stations to help get the wastewater to the treatment plant and

- The wastewater treatment plant itself is located in the former Pittsburgh Township (now the world-class, environmentally-sound Ravensview Wastewater Treatment Facility).

Interceptor sewers were added in the 1950s to intercept sewage before being discharged into the environment.

At the time, it was accepted during the design of the new collection and treatment system that it would not be able to handle all the flow, particularly during wet weather. The system was designed to handle flow during dry weather mainly, but to allow for “overflowing” to occur during heavier rains. This overflowing would ensure that overloading of the sewer system could be managed and that basement flooding could be prevented.

So, at every location where an existing combined sewer was located, the new interceptor sewer would capture the low flows, but when the flows became higher during rain or snowmelt, the additional volume would overflow from the collection system and continue down the original pipe to the environment.

While never measured, it is estimated that the 1950s improvements likely treated and captured anywhere between 60-80 percent of the annual average wastewater flow during wet weather.

1990s - Pollution control

In 1992, the first Pollution Control Plan (PCP) was completed for the City of Kingston. The report focused on identifying and addressing the primary sources of waterfront pollution in the City of Kingston, recognizing that both wastewater and stormwater runoff played a role. By this time, the City and neighbouring townships were installing primarily separated sewer systems, which meant that both a dedicated storm runoff collector and wastewater collector were built. Some replacement combined sewers were being built in the downtown core of the City, where separated sewers were deemed to be impractical or inappropriate.

The 1992 PCP ushered in an era of bypass reduction that continues to this day, recognizing that wastewater overflows are a significant contributor to lake and river pollution in the City of Kingston area, particularly adjacent to or downstream of the combined sewer area downtown. The Pollution Control Plan recommended numerous projects focusing on all manner of reduction techniques, all the while favouring “end-of-pipe” and “conveyance” control projects over "source-control" projects. Here is a list of projects that resulted from the findings of the first PCP:

- CSO storage tanks:

- Six smaller storage tanks in Sydenham Ward, located on West Street, Lower Union, Gore Street, Earl Street, William Street and Clarence Street. These were built to reduce overflows from these side-streets.

- One large 'end-of-pipe' storage tank located just west of Murney Tower in MacDonald Park (~6,000 cubic metre capacity). This was built to help reduce overflows around a bottleneck in the system.

- Pump station capacity upgrades:

- King Street Pumping Station (formerly called ‘O’Kill’).

- Portsmouth Pumping Station.

- Sewer projects: North End Trunk Sewer - twinning of specific low capacity sections.

The map below highlights recent projects that reduce sewer overflow events. Click on a feature to learn more about it.

2000s - Ministry of the Environment guidelines

After the mid-1990s introduction of MOE Procedure F-5-5, an update to the PCP was completed in 2000. Once again, a suite of new recommendations was provided, including:

- More CSO storage tanks: Two new large 'end-of-pipe' storage tanks were constructed: i) at the foot of Collingwood Street, south of King Street (west end of Breakwater Park, ~ 2,400 cubic metre capacity); and ii) just upstream of the River Street Pump Station in Emma Martin Park (~12,000 cubic metre capacity). These tanks intercept overflows from a couple major overflow points in the collection system.

- Pump station capacity upgrades: Dalton Avenue Pump Station (formerly called “North End Pump Station”) and River Street Pump Station. These received increased pumping capacities for increased conveyance to the Ravensview Wastewater Treatment Plant.

- Sewer projects:

- Twinning of the Harbourfront Trunk Sewer.

- Extraneous flow reduction in the Dalton Avenue Pump Station service area including remediation of the North End Trunk Sewer.

- Sewer separation (various locations).

MOE Procedure F-5-5

is a ministry guideline for benchmarking combined sewer system performance as it pertains to overflows.

It specifies recommended maximum overflow occurrences, durations and minimum levels of sewage capture for pollution control purposes.

- Sewer remediation: Cleaning and sealing of the leaky North End Trunk Sewer and the original Harbourfront Trunk Sewer.

It was around this time that sewer separation, as a true ‘source’ reduction technique, came to the forefront of the recommendations, supported fully by the 2010 Pollution Prevention and Control Plan Update, which went so far as to prioritize downtown areas for future sewer separation - as capital road reconstruction programs would permit.

Sewer separation became the default method of sewer replacement for road reconstruction for all but very specific circumstances where no storm outlet was available. By the mid-2000’s, all new sewers were constructed as separated systems and the vast majority of reconstruction projects of combined sewer areas used separated storm and sanitary sewers as well.

The graphic below illustrates the progression of sewer separation since approximately the time of amalgamation, around the year 2000. It shows the separation completed up until 2023.

The 2010 Pollution Prevention and Control Plan Update also introduced the benefits of conducting “extraneous flow reduction” projects to help with reducing the wet-weather contribution from existing separated sewers. Extraneous flows are caused by otherwise clean storms or groundwater entering the sewer system through leaks or illegal connections. These are “leaky” sewers that generally do not have intended storm connections, yet they are found to react to wet weather more than expected for a separated system. Techniques used for reducing these extraneous flows are numerous but include works on the public and private sides, including such things as:

- Illegal private-side drainage sources like roof downspouts, sump pumps and foundation drain connections to the sanitary sewer (learn more about Utilities Kingston Preventative Plumbing financial assistance program);

- Identification and removal of “cross-connections,” which include things like improperly connected storm catch-basins, which ought to be going to the storm sewer;

- All manner of sealing the pipes and maintenance holes from leakage, including pipelining, grouting of pipe joints and cracks, as well as targeted spot repairs and service mouth connection repairs.

Learn more at our extraneous flow webpage.

Today, and moving forward…

The most recent (2017) update to the Pollution Prevention and Control Plan has directed us to focus on source control strategies as the preferred approach to sewage overflow reduction. Nowadays, all new and replacement sewers are comprised of two pipe networks - separated storm and sanitary sewers.

In the long run, as the City of Kingston reduces storm and groundwater contributions to the sanitary sewer at the source, the amount and frequency of sewage overflow will decrease since all the runoff once captured by the combined system is removed.

In 2019, the City Council supported a progressive approach to combined sewer elimination by endorsing a 20-year sewer separation plan, which is now in effect.

Utilities Kingston also has other significant initiatives that are happening now, all having an impact on the amount and frequency of sewage overflows in the City of Kingston:

- Portsmouth Sewage Pump Station redirect: This project, when complete, will direct the sewage away from the Portsmouth Pump Station from the Ravensview WWTP service area to the Cataraqui Bay WTTP service area. Doing so will unload the Harbourfront Trunk Sewer with approximately 1/5th of its sewage, thereby decreasing sewage overflows along this critical corridor. An additional benefit is prolonging capacity at Ravensview WWTP as well as reducing the number of times sewage from this service area is pumped, from three times down to only once. This is a long-term project that is expected to be completed by 2028.

- Sewer separation projects: As of 2023, Utilities Kingston and the City are in the process of planning for and undertaking three large and significant sewer separation projects. These include the following:

- Victoria Street (Johnson to Union), Earl Street (Victoria to Collingwood), Couper and Collingwood Street (Couper to Union) and Union Street (Victoria to Albert) - to be constructed 2023/2024.

- Princess Street (Division to Alfred) and Garrett Street - to be constructed in 2024.

- King Street West (Alwington to Centre) and Pembroke Street (Union to King W.) - to be constructed in 2025.

Check out a map of our capital projects.

Gore Street sewer separation: A small project is ongoing in 2023 to complete sewer separation in the Gore Street catchment, between Ontario and Bagot. This will eliminate one overflow point as well as decrease the amount of stormwater in the system. The existing overflow tank is being repurposed for stormwater retention.

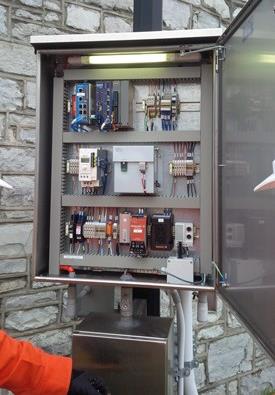

- Overflow management: Over the past 15 years (as of 2023), Utilities Kingston has been monitoring many of its overflow points to characterize how they work and how frequently they bypass. Since then, a considerable number have been plugged due to either sewer separation, and/or low volume/low frequency. At this time, not including emergency overflows located at facilities, there are 16 remaining overflow points in the collection system.

In 2016, these overflow points were all equipped with robust monitoring equipment that permits long-term monitoring and quantification of overflow events, in real-time. Utilities Kingston then created Canada's first real-time overflow status map. This was done for complete transparency and so that the public and stakeholders can make informed decisions whether to swim, fist or boat. After heavy rains, check our map! Utilities Kingston will still maintain its overflow log as well.