Causes of basement flooding

Why a basement might flood

Flooding of basements can occur any time. It can happen to anyone who has a basement, even if never flooded before. While most often flooding occurs during big rains or rapid snowmelts in the spring, it can occur even during dry weather.

There are a number of reasons why basements flood. Flooding can occur by seepage or flow through the walls or foundation floor, from surface water sources, or by a sanitary or storm sewer backup.

Please remember:

- Basements are inherently prone to flooding. They are, by definition, the lowest level of a building, typically built partly or entirely below ground level.

- Groundwater is water that is naturally located below the ground’s surface. The groundwater level can be, at times, above the level of the basement floor. In some locations, groundwater can be above the level of the floor at all times.

- Sewers are also located in the ground. This includes all varieties – storm, sanitary, and combined. While in most cases, sewers are below the level of the basement, the water level in the sewers can be, at times, above the level of the basement floor.

- Gravity does its best to move water from high to low. If either the groundwater level or sewer level around your home is above the basement floor, gravity will try to move that water into your basement. A crack in the foundation floor, for example, provides gravity with a perfect path for water to be pushed into the basement. Sanitary sewers always have a path to the home, by design, and it is called the sanitary sewer lateral. While under normal conditions, the lateral allows water to flow from your home to the sewer, there is the potential for water to move from the sewer toward your home.

The circumstances described are shown in Figures 2 and 3, which are discussed in more detail below.

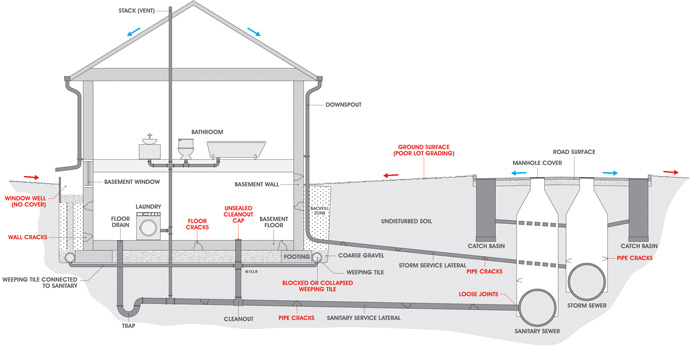

In order to understand why a basement might flood, it is important to show the more common pathways, intentional or not, that permit water to flow into or around your basement. Figure 1 indicates a typical home in the City of Kingston, and how it is serviced during normal conditions. Not all homes in Kingston have a storm sewer lateral (as shown in the figure), but most just have a single sanitary sewer lateral.

Figure 1 highlights common problems (in red) that all might contribute to a higher risk of flooding. Most are on private property, or are things that are within a home owner’s ability to change - whether by regular maintenance or by specific projects to eliminate or reduce potential flooding sources. Some of these problems include:

- Poor lot grading: the sloping of the land is promoting water flow toward the house

- Unmaintained foundation: cracks have developed that allow water to seep in

- Problems with pipes: both the weeping tile and laterals have problems

Flooding during dry weather

Most flood events do happen during wet weather, but it is quite possible for a flood to occur during dry weather too. Three of the most common reasons are as follows:

-

A blocked or failed sanitary lateral. The sanitary sewer lateral, just like the shingles on your roof, or your paved driveway, is a feature that will degrade over time. As a lateral degrades, several things can happen. For example, tree roots might penetrate and the lateral might collapse because of gradual deterioration. These scenarios can block the lateral, resulting in a sewage backup.

In this case, it will be your own home’s domestic wastewater that floods your basement. The only way for the wastewater to drain becomes the lowest fixture in the home – usually the floor drain or a basement level shower stall, sink or toilet. Your lateral, just like your roof, your driveway or windows, needs maintenance, and ultimately needs to be replaced or rehabilitated. Talk to a licensed plumber, who can carry out an assessment.

Another reason for blockage of a sanitary sewer is simply due to what is being flushed down the toilet. Our Toilets and Drain page has a list of things not to put down your drain, or flush down your toilet. Toilets are for human waste and toilet paper, and that is pretty much it!

-

Foundation drainage failure. Subdivisions are sometimes constructed in lower-lying areas that are generally wetter than others. In such cases, the foundation drainage system, whether by gravity or by pump, must work continuously to keep the ground water level around the foundation lower than the basement floor.

Just as with sewer laterals, gravity foundation systems, often called weeping tiles, may degrade over time or get plugged by fine sediments. As a result, the ground around the foundation will cease to drain itself by gravity.

In other cases, sump holes in the foundation are constructed to accommodate a sump pump. These devices pump out the water around the foundation and either discharge it to the lawn, storm sewer, or illegally to the sanitary sewer. Discharging a sump pump to the sanitary sewer is illegal, by way of City By-law No. 2008-192. It is possible for these pumps to fail, or simply be unable to keep up with the incoming water, or get plugged.

This flood type will be discussed further in the wet weather section.

-

Water supply-line break or hot-water tank failure. Sometimes, a flood is due to a break in the home’s internal water supply plumbing or failure of the hot-water tank. This can result from aging plumbing or equipment, a puncture of a pipe during construction, or freezing-induced splitting of a pipe.

Flooding during wet weather

Flooding during wet weather is far more common that flooding during dry-weather. Rain, ground-thaw and snowmelt put a heavy load on drainage systems, including the storm and sanitary sewers found underground. With the additional water on the surface and underground, there are a number of reasons why a basement might flood.

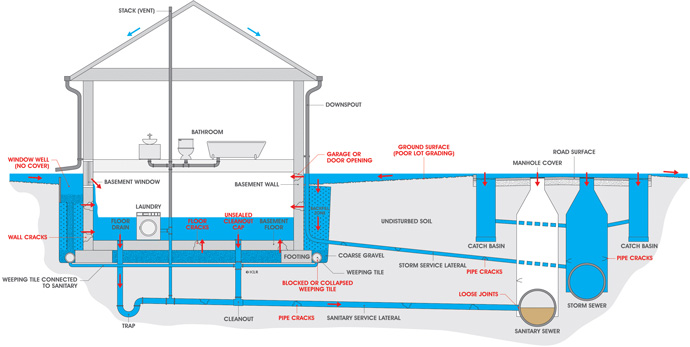

- Surface inflow, or overland flooding. During periods of heavy rain or rapid snowmelt, surface water may pool around the house, or accumulate in hard surface depressions such as driveways or roads adjacent to a home. During extreme weather events, this water can flow into the home. Close proximity to a natural stream or road-side ditch can also present a risk. Generally, proper grading on the property will reduce the risk of surface water getting into your home. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

One of the most common causes of water pooling up against a home is failure to maintain functioning eavestroughs and downspouts. If those roof drainage systems fail, or freeze-up in the winter, they can cause all water from the roof to drain right beside the house and seep along the foundation wall and possibly into the basement. See our webpage on how to protect your home from basement flooding.

-

Foundation drainage failure. Homes usually have some form of a drainage system built around them. This safeguard promotes the movement of water away from the basement and blocks the entry of water into the building.

For the purposes of our discussion, the waterproofing aspects of a foundation are considered part of the foundation drainage system. Within this category, there are three main causes for basement flooding, all generally a result of excessive groundwater around the foundation, as illustrated in Figure 2:

-

- Seepage. If the water table rises, water can enter the basement via cracks, holes and other unintended flow paths. This is generally considered to be part of the aging process of the home and the materials used to build it. Regardless of the condition of the drainage materials and pipe work around the foundation, if water can enter the foundation floor or walls via cracks and holes or other defects, it likely will do so during heavy rains, ground-thaw or snow-melt periods, when there’s lots of water in the ground. Settlement of the lot grading around the building and downspouts discharging run-off water too close to the home can increase the quantity of water around the foundation and increase the risk of water entering via cracks.

- Sump pump failure. If your basement is equipped with a sump and sump pump(s), it can mean that the foundation drainage system of your home requires some assistance to keep up with the groundwater around it, or it simply cannot drain adequately by gravity to the surrounding ground or storm sewer. New homes are required to have sump pumps in these situations. Sump pumps, when working properly and adequately maintained, can safely pump excess water above the foundation and away from it. Ideally, this water should be routed to the lawn or storm sewer. If the pumps cannot keep up, or fails to operate (perhaps due to a power failure, or malfunction), the groundwater level around the foundation can rise to the point that it flows up and out of the sump onto the basement floor.

- Weeping tile failure. Over time, the foundation drainage system can deteriorate. As a result, the weeping tile system can fail. This may be, due to a partially- or fully-collapsed pipe, or due to sediments plugging the pipes. If the weeping tile fails, the drainage of water around the foundation is either impeded or blocked altogether. As a result, the groundwater level around the foundation gets too high and it may spill into the basement via the sump, if one exists, or via leaks in the foundation. In situations where there are leaks in the sewer lateral or plumbing beneath the foundation, groundwater can inundate the sanitary lateral and restrict the flow of sanitary wastewater. This could result in both groundwater and/or wastewater entering the basement by way of the floor drain or lowest sanitary fixture.

- Sewer backup. Most homes in the City of Kingston only have one connection to the sewer system, and that is the sanitary sewer lateral. However, newer homes built in the last 20 years, as well as some other older neighbourhoods, have storm sewer laterals as well, for the purpose of foundation and downspout drainage (See Figure 1.)

These laterals form either one or two intentional direct connections to the municipal storm and/or sanitary collection systems. The municipal storm and sanitary systems operate well and are maintained through a variety of municipal maintenance programs.

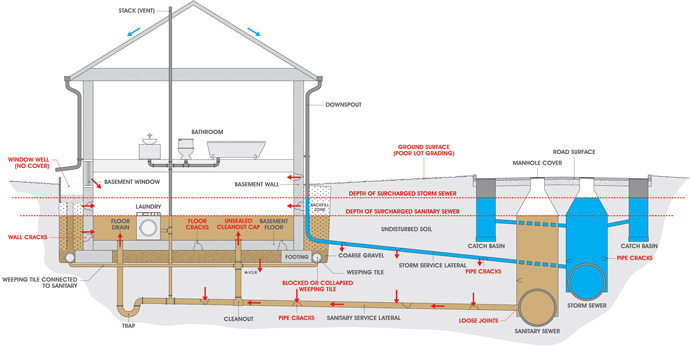

However, when a blockage occurs, or when the systems are overloaded during heavy rains, a sewage backup can occur into a building, as per Figure 3. Here are a few reasons why:

- Sewers are full. When the sewers are full, this is called a “surcharged condition”. It means the pipe system is full and the water level in the manholes may rise well above the top of the pipe. If the sewage level in the system exceeds that of your basement, flows can be blocked, or worse, sewage can flow towards your home (see Figure 3). When this occurs, the wastewater may enter your basement by way of the lowest fixture, which is usually a floor drain, shower drain, sink, washbasin or toilet.

The underlying cause of this is excess water in the sewer system, which ultimately overloads the sewer with more water than it was designed for. Excess water generally comes from leaks in sewer-mains and sewer laterals, inflow from surface features as well as illegally-connected, private-side sources including foundation drains, sump pumps and downspouts. The technical term for this is “extraneous flow” or “inflow and infiltration”. For more detail, visit our Extraneous Flows page.

- Flow restriction. Any situation that puts additional flow into the sewer lateral may make the problems of a partially- or fully-blocked sewer lateral worse. If flow is restricted, there is more chance a sewer backup can happen.

In summary, there are several different circumstances that can result in basement flooding.

If you have experienced floods and wish to learn more about why it happens and how to reduce the chance of it happening again, consider reviewing the following videos, produced by the ICLR:

Reducing the risk of basement flooding

Additional resources

- How to Protect your Home against Basement Flooding (Utilities Kingston, 2011)

- Handbook for Reducing Basement Flooding (Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction, 2009)

- Practical Measures for the Prevention of Basement Flooding Due to Municipal Sewer Surcharge (Canada Mortgage & Housing Corporation, Research Highlight, January 2004)